A Hindu King Was Cremated Five Years Before The First Legal Cremation in Italy

Kolhapur Maharaja Rajaram passed away in Florence during his trip to Europe in 1870

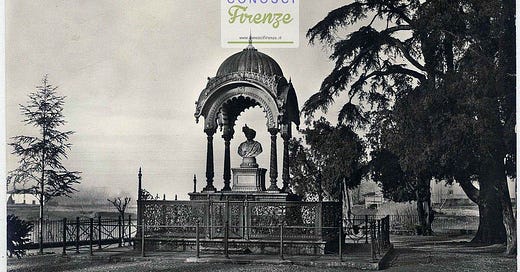

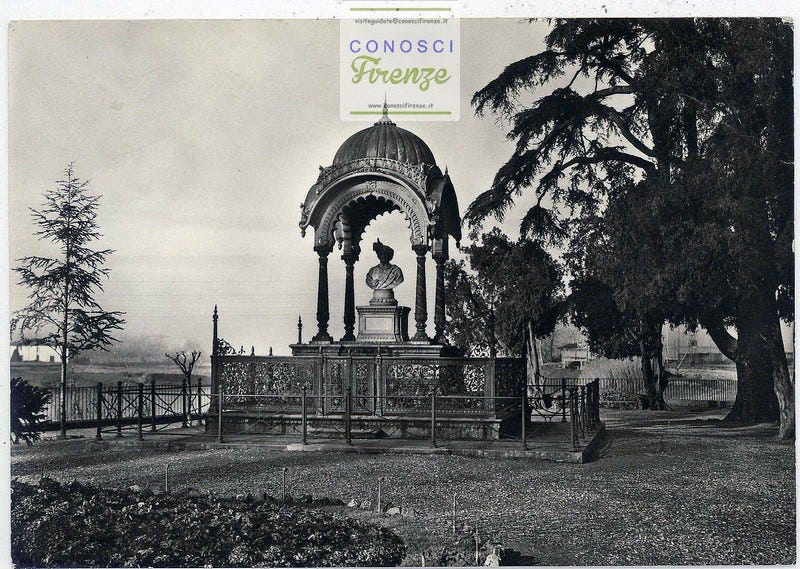

At the west end of Cascine Park in Florence, there is a monument called the Monumento all'Indiano, or the Monument to the Indian. Dedicated to the memory of a Maratha king, Rajaram Chhatrapati, it features a Chhatri over a bust.

This is the story of the cremation of 21-year-old King Rajaram, who tragically died from an illness in 1870 while coming from London. Rajaram's cremation raised great curiosity in Italy and the UK at the time.

Rajaram-II (1850–1870) was king of Kolhapur (1866 to 1870) and belonged to the Bhonsle dynasty of Maharashtra (India). He ascended the throne in 1866 at 16 and was entitled to a 19-gun salute by the British Raj.

Rajaram was very modern in his thinking. He decided to travel to Europe to learn more about the Victorian education system and medical facilities. He hoped to use this knowledge to benefit the people of his state. Rajaram's three wives were accompanying him.

In London, Prime Minister William Gladstone hosted him. After learning that the king admired the arts, Gladstone suggested that he should visit Paris, Nice, Genoa, and Florence. Unfortunately, the Franco-Prussian War had interrupted the usual route, so Rajaram went through Belgium and Germany and got to Florence (Italy).

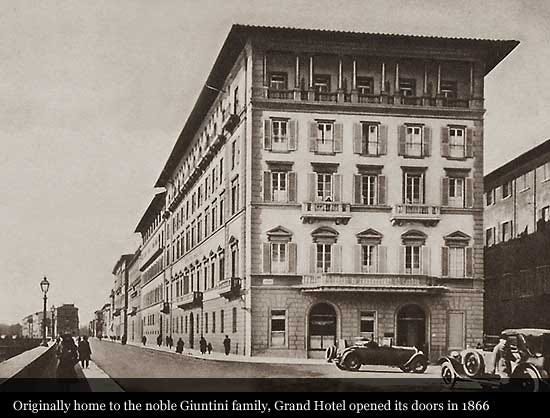

The king stayed at the Grand Hotel in Palazzo Giuntini, located in Piazza Ognissanti on the bank of the River Arno. After his arrival at the hotel, he complained of fever, fell seriously ill, and died suddenly on November 30, 1870. It is believed that he died of a lungs’ infection, but there is some dispute about the cause of his death.

Keeping the tradition, the king's family insisted that he be cremated according to Hindu rites along the bank of the River Arno. The city government of Florence was horrified to be asked to permit a cremation banned at the then-capital of Italy. Then British Consul Sir Augustus Paget came to the rescue of Rajaram's attendants. On his insistence, the Council of Ministers at Rome made an exception, but Florence mayor Ubaldino Peruzzi de' Medici prescribed that the cremation be carried out late at night.

A carriage drew Rajaram's mortal remains from his hotel to the pyre at the “extreme point of the Cascine…a deserted and open esplanade.” A large number of spectators accompanied the procession.

One of the oldest regional newspapers in Italy, La Nazione reported: “He was attended by Professors Ghinozzi, Cipriani, and Wilson but despite the indefatigable and intelligent care given to him by the distinguished physicians, he succumbed at the age of 20.”

The Municipality of Florence prepared a detailed report of Rajaram's cremation.

“Dressed with pearls and wrapped in a gold-embroidered shawl, his body was placed on a wood pyre three feet high, his face uncovered and turned east toward India. More wood was added around the sides of the corpse; his face was anointed with ghee, camphor and sandalwood paste; and a gold coin and betel nut were placed in his mouth. Soon after 2:00 am, the pyre was lit, the flames carried skyward by a brisk wind. At 5:00 am, the skull was still visible, “bare and blackened,” and not until 10:00 am was the cremation complete. The next day fragments of charred bone (the phul) were gathered from the site and placed in a porcelain vase. Covered with a red cloth and sealed with wax, these remains were to be taken back to India for immersion in the Ganges. The ashes were committed to the Arno.”

Historian David Arnold says this “also provides evidence of the manner in which ashes and bone fragments were placed in various receptacles—ceramic jars, wooden boxes, metal urns—for storage, transportation, and further commemoration.” The Gazetteer of the Bombay Presidency records that the funeral rites of Rajaram were almost identical to those of Brahmins.

Rajaram’s cremation started a political debate in Italy. According to historian Thomas Laqueur, “Nowhere was cremation more politically and religiously charged than in Italy. The Italian pioneers of cremation were doctors, scientists, progressives, Positivists; they were republicans and supporters of the Risorgimento; they were anti-clerical. Most important – or rather, representing all these ills, from the perspective of the church – they were Freemasons.”

The first legal cremation in Italy took place six years later in 1876 in Milan's Cimitero Maggiore. The German businessman Alberto Keller's body was cremated two years after his death in the hope that when technology reached an advanced enough stage, he could be cremated.

Four years after Rajaram’s death in 1874, a monument was built in Cascine Park with a polychrome bust of the king Rajaram. The British government financed this Indo-Saracenic monument's cost, which employed the sculptor Charles Francis Fuller.

The architect Charles Mant designed the pavilion of this monument. Rajaram commissioned Mant to construct several public buildings in Kolhapur before he left India. This monument's base is inscribed in English, Italian, Hindi, and Punjabi and mentions the details of his death.

After more than a hundred years, in 1972, a bridge was built near the monument by the name of Ponte all'Indiano or the Bridge of the Indian. Opened in 1978, it links the suburbs of Peretola to the north of the river to Isolotto to the south.

King Rajaram kept a diary, in which he has left an account of his journey to Europe. It was published after his death in England under the title-Diary of the Late Rajah of Kolhapur, During His Visit to Europe in 1870. In this diary, he writes about his journey across the English Channel, his life and mansion near Hyde Park in London, his visits to watch Shakespeare's plays and the Royal Geographical Society. He also mentions visits to the library at Oxford University, Kew Gardens, and hunting matches, as well as a visit to Westminster.